The Victoria and Albert museum in the United Kingdom are returning to Ghana, the Asante gold regalia because the spirits have been haunting them.

A historian and linguist at Manhyia Royal Palace in the Ashanti Kingdom, Teacher Kwadwo Sarfo Kantanka has told Sompa Tv in an interview that the spirits in the gold ornaments are giving them sleepless nights and therefore their decision to return the ornaments back to the rightful owners (Asanteman).

According to the historian, the king of Ashanti Kingdom, H.R.M Otumfour Osei Tutu the 2nd has had discussions with them on the return of the objects taken from the Ashanti’s in the olden days.

Recall.

The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) is likely to return Asante gold regalia to Ghana after a recent visit there by its director Tristram Hunt. These treasures had been seized during a British punitive raid in 1874.

Although international attention is now focused on the restitution of Benin bronzes to Nigeria from European and American collections, items from the Asante kingdom are arguably of equal significance. Together, Benin and Asante (now in Ghana) represent two of the greatest West African cultures. A return of treasures to Ghana by the V&A will inevitably increase pressure on the British Museum, which holds a much larger Asante collection.

The British colony of the Gold Coast was expanded in 1872 and conflicts then intensified with the Asante kingdom, which lay to the north. In January 1874 British troops entered Kumasi, the Asante capital. Queen Victoria’s forces looted and blew up the palace of the king (Asantehene), Kofi Karikari. They then demanded 50,000 ounces of gold, nominally to recover the expenses of the punitive raid. The seizure of the gold regalia stripped the Asante king of his symbols of government. Tensions continued over many years and further treasures were seized during later military campaigns in 1896 and 1900.

Hunt, in the V&A’s latest annual review, writes: “I visited Ghana to begin conversations about a renewable cultural partnership centred around the V&A collection of Asante court regalia, which entered the collection following the looting of Kumasi in 1874. We are optimistic that a new partnership model can forge a potential pathway for these important artefacts to be on display in Ghana in the coming years.”

On his visit in February, Hunt held discussions with both the Ghanaian ministry of tourism, arts and culture and the current Asante king, Osei Tutu II.

Most UK national museums are not normally able to deaccession, in the V&A’s case because of restrictions incorporated in the 1983 National Heritage Act. Hunt favours a loosening of this prohibition and with next year’s 40th anniversary of the act, he would like to see a debate over deaccessioning.

Long-term loans

For the present, the V&A can only offer a long-term loan of Asante treasures, but eventually such loans might lead to a transfer of legal ownership. We can report that the V&A-Ghanaian discussions were partly facilitated by Ivor Agyeman-Duah, a Kumasi-born historian of Asante art and architecture. He served as an adviser to John Kufuor, a former president of Ghana (2001-09), and was a former director of the Ghana Museums & Monuments Board.

One of the sensitive issues that needs addressing is whether treasures returned from Britain should be displayed in the national capital, Accra, or the Asante capital, Kumasi.

Agyeman-Duah tells The Art Newspaper that he believes it is important that looted Asante objects should be returned to where they were seized: “It is appropriate that they go to the palace in Kumasi.”

The venue there would be the Manhyia Palace Museum, a building erected in 1925, which served as the royal residence until 1970. In 1995 it became a museum. It has been closed since last year for refurbishment, including upgrading security and environmental conditions, which will pave the way for international loans.

Golden fleeced: works in UK museums

The greatest part of the V&A’s Asante collection comprises 13 pieces of looted Asante court regalia. These were sold by the British army through the London crown jeweller Garrard.

They include a decorated gold pectoral “soul” disc, shaped like a flower, which would have been worn by priests involved in the ritual purification of the king’s soul. There is a also a pear-shaped pendant, either worn or possibly attached to a state sword or stool. The remaining pieces of regalia are of gold.

The British Museum’s collection of Asante objects is much larger, including 105 items that were seized in 1874. Of these, 83 were purchased from the crown agents for the colonies, 12 from Garrard and ten elsewhere. A further 12 pieces were acquired after an 1896 raid.

Among the most poignant objects in the British Museum’s collection is a large gold “soul” disc. When acquired by the Marquess of Exeter in 1874 he had it framed by Garrard in an impressive gold surround, made in London. On the reverse it is inscribed, along with the aristocrat’s crest: “The gold ornament in the centre of this dish is a portion of the indemnity paid by the Ashanti King Coffee Calcalli to Her Majesty’s Forces.” This transformed a sacred Asante religious object into an English war trophy. Perhaps surprisingly, the object was bought by the British Museum from the owner’s descendants in 1973, nearly a century after the looting.

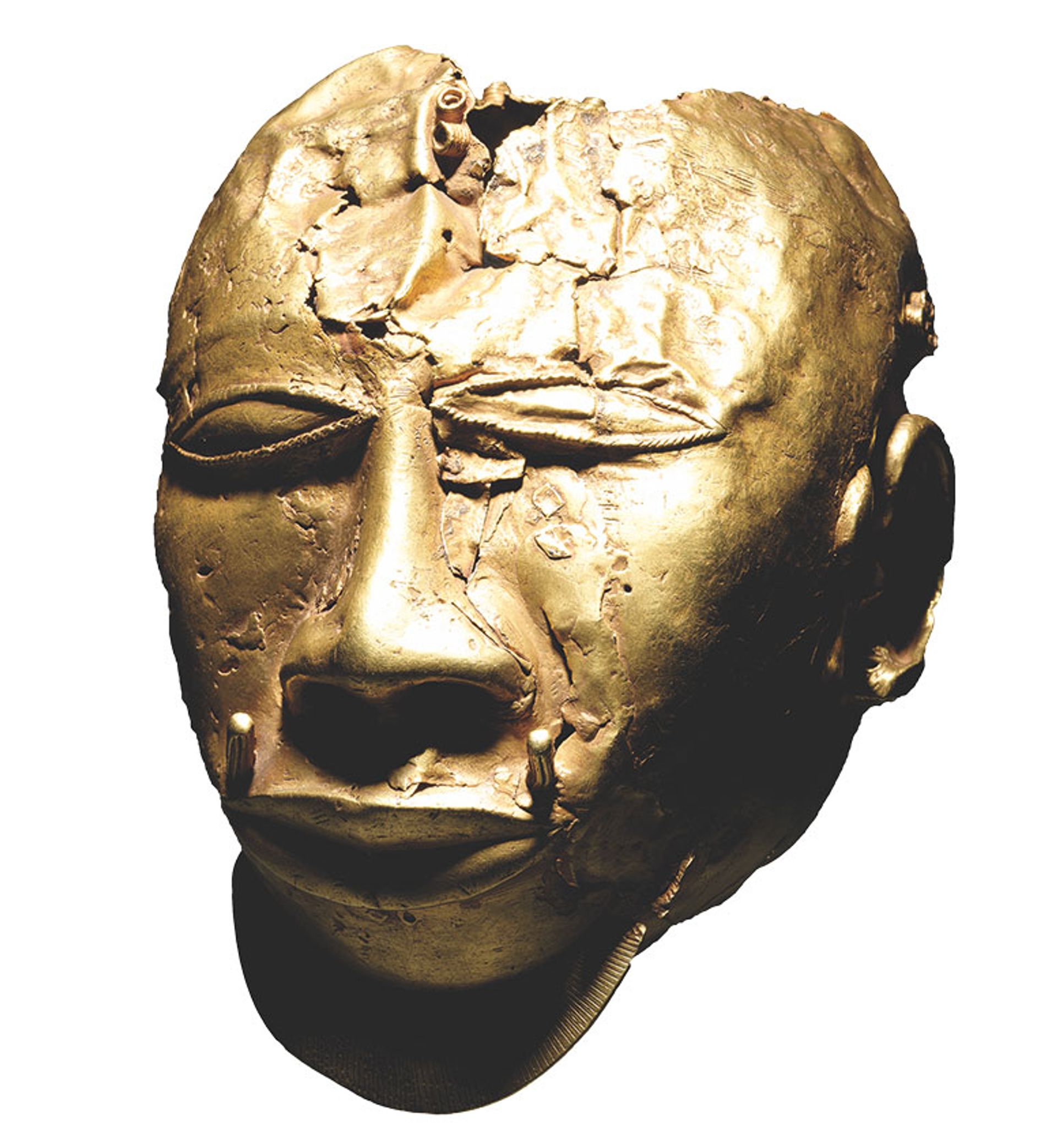

The Wallace Collection has a stunning gold Asante trophy head which is the largest known piece of historic gold work made in Africa, outside Egypt. This was bought by Richard Wallace in 1874.

London’s National Army Museum owns an important ceremonial bowl which stood outside the royal mausoleum. This was once erroneously said to have been used to collect the blood of beheaded sacrificial victims, a reflection of British colonial attitudes in the 19th century.

The Royal Regiment of Artillery is believed to own an important Asante gold ram’s head. It is set on an elaborate stand, made in London in 1875, which includes three Atlantean figures of Africans.

When The Art Newspaper asked for further information, we were told that the regiment “do not circulate details relating to their private property”.

Other Asante pieces are in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, Leeds Museum and the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford.

In 1974, the centenary of the looting, the then Asante king, Opoku Ware II, asked for “the return of regalia and other items removed from our country by British expeditionary forces in 1874, 1896 and 1900”. Although that claim was made nearly 50 years ago, it now looks likely that the V&A will be taking the bold step of leading the way in acceding to this request.

The V&A is not commenting further, although an announcement is likely later this year.

A British Museum spokesperson says that a formal claim was received in 1974. Since then “there have been several spoken requests, most notably by the current Asantehene, during the visit of the deputy director of the British Museum to Kumasi in 2010”. The spokesperson says that there is “a cordial working relationship with the Asante Royal Court through the Asantehene and the Manhyia Palace Museum committee”.

Discussions have been held with the Asantehene, with both parties expressing the “ambition that objects from the British Museum collection might travel on loan to the Kumasi museum”.

Source…www.sompaonline.com/Eric Murphy Asare

Sompaonline.com offers its reading audience with a comprehensive online source for up-to-the-minute news about politics, business, entertainment and other issues in Ghana

Sompaonline.com offers its reading audience with a comprehensive online source for up-to-the-minute news about politics, business, entertainment and other issues in Ghana