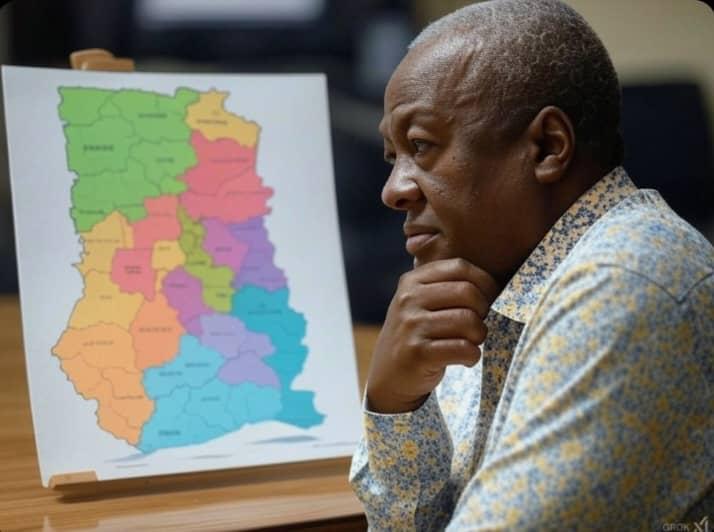

Ghana, a West African nation with a population of approximately 33 million, has made significant strides in managing infectious diseases over the decades. However, the rise of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases (ERIDs) poses a formidable challenge to its public health system. Diseases such as Human Metapneumovirus, Cholera, Cerebrospinal meningitis (CSM) and the re-emergence of previously controlled pathogens like poliovirus highlight the need for robust surveillance, research, and response mechanisms. While international donor support, particularly from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), has played a pivotal role in bolstering Ghana’s health infrastructure, the question remains: Where does Ghana stand if such external support were to diminish or disappear entirely? This article explores Ghana’s current capacity to address ERIDs, focusing on its research institutions, public health systems, population health research, and university research units, while weaving in relevant statistics.

The Burden of Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases in Ghana:

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) are newly identified pathogens or those increasing in incidence, while re-emerging infectious diseases (REIDs) are known pathogens that resurface after a period of decline. In Ghana, malaria remains the most reported infectious disease, with an estimated 9.6 million cases annually, accounting for roughly 30% of outpatient visits. Beyond malaria, zoonotic diseases like Lassa fever and influenza, as well as re-emerging threats like polio (last reported in 2008, re-emerged in 2019), underscore the dynamic nature of Ghana’s disease landscape. The COVID-19 pandemic, with over 171,000 confirmed cases and 1,462 deaths as of early 2025, further exposed vulnerabilities in Ghana’s health system, despite a relatively effective initial response. Without donor support, particularly from USAID, which contributed approximately $105 million to Ghana’s health sector in 2023 alone, the country’s ability to detect, prevent, and respond to these threats could falter. USAID has supported initiatives like influenza surveillance, HIV/AIDS control, and malaria prevention, including the distribution of 4.5 million bednets annually. The absence of such funding would shift the burden entirely onto Ghana’s domestic resources, raising concerns about sustainability and capacity.

Research Institutions in Ghana:

Ghana hosts several research institutions critical to combating ERIDs, though their scale and funding remain limited without external support. The Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR), established in 1979 under the University of Ghana, is the country’s premier biomedical research center. With over 200 staff, including 50 PhD-level researchers, NMIMR conducts studies on viral zoonoses, neglected tropical diseases, and respiratory infections. It serves as the regional hub for the CDC’s Influenza Division in West Africa, monitoring 36 sentinel sites nationwide. The Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine (KCCR), affiliated with the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), is another key player. Employing around 150 researchers and support staff, KCCR focuses on infectious diseases like tuberculosis and neglected tropical diseases, often in collaboration with international partners. Other institutions, such as the Navrongo Health Research Centre (NHRC) in the Upper East Region, with approximately 100 staff, emphasize field-based epidemiological studies. Collectively, Ghana has about 10 major health research institutions, employing roughly 500–600 researchers. However, these institutions rely heavily on donor funding—USAID, the European Union, and the Wellcome Trust, among others—for equipment, training, and operational costs. Without such support, their ability to conduct cutting-edge research, maintain laboratory infrastructure, and train personnel could erode significantly.

Public Health Infrastructure:

Ghana’s public health system, anchored by the Ghana Health Service (GHS), oversees approximately 4,000 health facilities, including 16 regional hospitals and over 3,000 community-based health planning and services (CHPS) compounds. The GHS employs about 80,000 health workers, including 2,500 doctors and 20,000 nurses, serving a doctor-to-patient ratio of 1:8,000—well below the World Health Organization’s recommended 1:1,000. The Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system, implemented since 2002, tracks priority diseases across 260 districts, but its effectiveness is hampered by inadequate staffing, funding, and diagnostic capacity.

The National Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC), operationalized with CDC and USAID support, coordinates responses to outbreaks, supported by four regional PHEOCs. In 2023, the GHS reported investigating over 50 outbreaks, including meningitis and yellow fever, demonstrating some capacity for response. However, the system’s reliance on external aid for supplies, training, and infrastructure—such as the Tamale Infectious Disease Treatment Center—suggests that a withdrawal of donor support could cripple rapid response capabilities.

Population Health Research:

Population health research in Ghana focuses on understanding disease patterns and risk factors across its diverse populace. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) estimates that 45% of Ghanaians live in rural areas, where access to healthcare is limited, exacerbating the spread of infectious diseases. The Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS), conducted every five years, provides data on disease prevalence, with the 2022 survey noting a 14% prevalence of hypertension alongside persistent infectious disease burdens.

Institutions like the NHRC conduct longitudinal studies, such as the Navrongo Health and Demographic Surveillance System, tracking over 160,000 individuals annually. These efforts reveal the dual burden of infectious and non-communicable diseases, with 25% of deaths in 2023 attributed to infectious causes and 40% to chronic conditions. However, funding for such research often comes from donors like the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), and domestic investment remains insufficient to sustain these programs independently.

University Research Units:

Ghana’s universities play a vital role in infectious disease research, with over 20 units across 10 public institutions. The University of Ghana’s School of Public Health (SPH), with about 40 faculty and 200 graduate students, leads in training and research on infectious disease control and health systems. The Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) hosts KCCR and has a Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences with 30 researchers focused on drug resistance in pathogens like Plasmodium falciparum.

The University of Health and Allied Sciences (UHAS) in Ho, with roughly 25 faculty in its School of Public Health, conducts community-based studies on zoonotic diseases. Collectively, these universities produce about 50–60 peer-reviewed papers annually on infectious diseases, though many projects depend on international collaborations funded by USAID, NIH, or European grants. Without such support, research output and training capacity would likely decline, stunting innovation and expertise development.

Ghana’s Standing Without Donor Support:

Ghana’s domestic health budget for 2024 was approximately $1.2 billion (15 billion GHS), representing 6% of GDP—a commendable effort but insufficient to fill the gap left by USAID’s $105 million annual contribution. The loss of donor support would likely strain surveillance systems, reduce laboratory capacity (currently 15 accredited labs for COVID-19 testing), and limit training programs like the Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program (FELTP), which has trained over 400 epidemiologists since 2008 with CDC backing.

While Ghana has demonstrated resilience—e.g., managing the 2022 Marburg outbreak with NMIMR’s rapid diagnostics—its reliance on external resources for vaccines, diagnostics, and technical expertise remains a critical vulnerability. The absence of a formalized One Health policy, integrating human, animal, and environmental health, further complicates independent action against zoonotic threats.

Conclusion:

Ghana stands at a crossroads in its fight against emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Its research institutions, public health infrastructure, population health research, and university units provide a foundation for progress, but their capacity is deeply intertwined with donor support. Without USAID and similar partners, Ghana risks a backslide in disease surveillance, research innovation, and outbreak response. To secure its future, Ghana must prioritize domestic funding, strengthen intersectoral collaboration, and build self-reliance—a tall order, but one essential for safeguarding its population’s health in an increasingly unpredictable world.

Writer:

Prince Ishmael Dimah, MAPH

Dietitian, Nut.

Sompaonline.com/Nana Yaw Boamah

Sompaonline.com offers its reading audience with a comprehensive online source for up-to-the-minute news about politics, business, entertainment and other issues in Ghana

Sompaonline.com offers its reading audience with a comprehensive online source for up-to-the-minute news about politics, business, entertainment and other issues in Ghana